The Australian Sappers in Amiens

by Hannah Noye

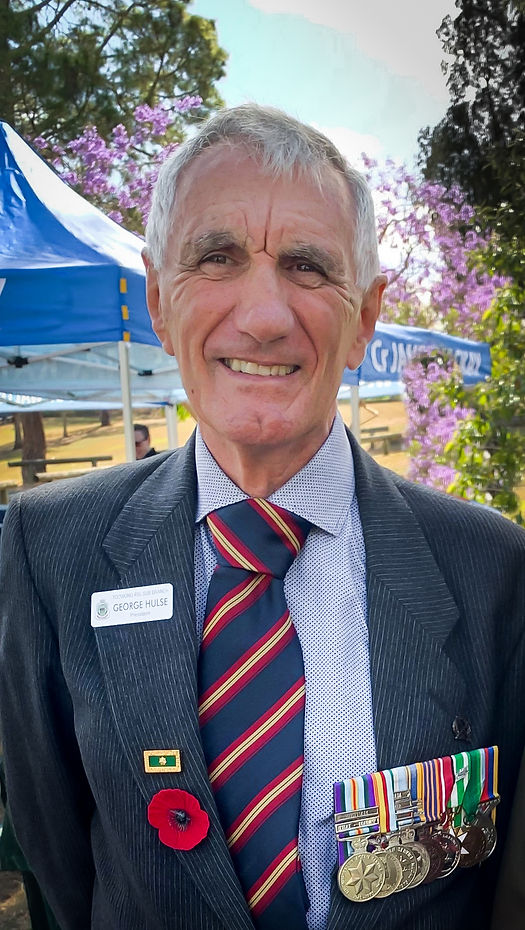

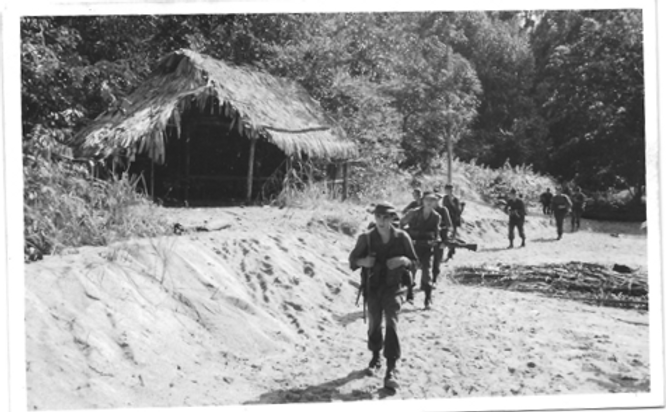

Australian Troops photographed at the Battle of Amiens

Lieutenant Colonel George Hulse OAM has lived his life serving the country of Australia as a combat engineer. As a Vietnam War veteran, George became the President of the First Field Squadron Group Association who are also known as the ‘Tunnel Rats’. These were the soldiers who entered into deeply dug underground tunnels and bunkers where they recovered masses of enemy information, ammunition and other materiel vital to the enemy war effort. At that time, these Sappers thought themselves as the first of their kind, but in fact George Hulse and his Association’s historians found out that there were a group of Australian Sappers who did the same thing during World War One.

From there the Corps of Royal Australian Engineers investment in preserving the memory of these men has grown immensely, and lead to today’s efforts to establish a friendship Bridge in Amiens, France; the place from where Australian Sappers marked a significant role in Australian military history.

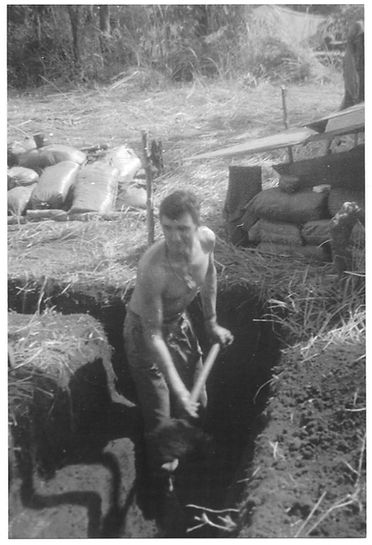

George Hulse pictured in the Vietnam War

George recounts the story of one day in particular, the 8th of August, 1918 – the Battle of Amiens. At 4:20am in the morning the British, French, and Americans jointly attacked the Germans to great success.

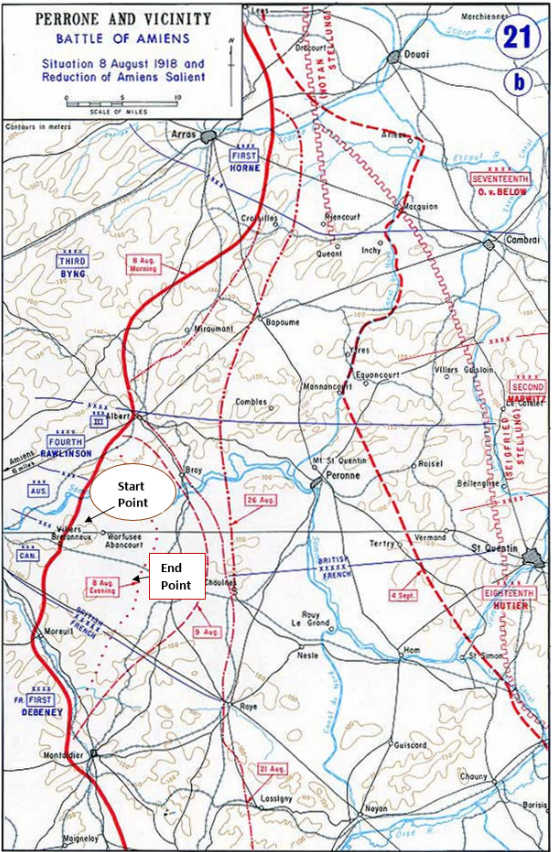

On a roll, the armies of course wished to continue their success and push back the Germans farther. The Australian troops were given 4 days to get from Villers-Bretonneux to the town of Harbonnieres, a distance of about 15 kilometres – but these brave men were able to succeed in their task in only 8 eventful, courageous hours.

The above map shows the distance travelled by the Sappers within 8 hours – a distance rife with danger and enemy forces

The role of a Sapper (a combat engineer) is vastly overlooked and undervalued – they are the first soldiers into a dangerous situation and the last to leave. They facilitate the crossing of dangerous lands, the defusing of difficult situations, and more while under life-threatening circumstances. On this particular day, one group of Sappers led by Lieutenant Ralph Hunt, and including his Body Guard Sapper George Hook, were tasked with building three bridges to cross the Somme river near the town of Cerisy. One of the bridges, codenamed ‘Cherry Bridge,’ which had been assumed to be demolished was in fact still standing, and so the Sappers captured it. Unfortunately above them on Chipilly Spur were a number of Germans unaffected in the morning assault, and they shot down George Hook who despite the best effort of Hunt died of his wounds.

The location where the team was supposed to erect ‘Sapper Bridge,’ was thought too dangerous, and as such Hunt left just 6 men to guard Cherry Bridge and pushed forward to find a better spot for his bridges with the rest of the Sappers under his command.

At this moment, only 500 metres from the remaining 6 Sappers at Cherry Bridge, loud fighting and gunfire commenced, and 2 of these men, Sapper Arthur Dean and Sapper William Campbell, were sent to investigate. The scene they came upon was that of the London Fusiliers being brutally machine gunned from a German position farther up the hill.

Despite being vastly outnumbered these two brave men decided that they had to do something. They penetrated behind the German position and making as much noise as they possibly could, entered the scene. Throwing bombs and doing their best to create the illusion of more soldiers, the two Australian Sappers attacked the German position and it worked! The German officer thought they were surrounded and surrendered, giving the British the chance to quickly take back control of the situation.

These two sappers were nominated for the Victoria Cross, surely warranted by their remarkable bravery, but instead only received the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

These events were not the only miraculous successes to occur on this day however. The Sappers made their way on to a place called ‘Warfusee.’ There they found a Command Post dug under the ground – the Sappers entered the dugouts. And Viola – there they found 5 senior German officers totally ignorant to the defeat of their men and subsequent advancement of the Australian troops. After making the appropriate capture of these important people, the Sappers continued on the town of Bayonvillers, which was being abandoned in a rush by the Germans who realised the Australians were en route. In their haste they failed to take with them their maps and other documents with critical information about battle strategy and the location of their stores dumps.

From here they continued to Harbonnieres where it was taken by the Australian 31st Infantry Battalion.

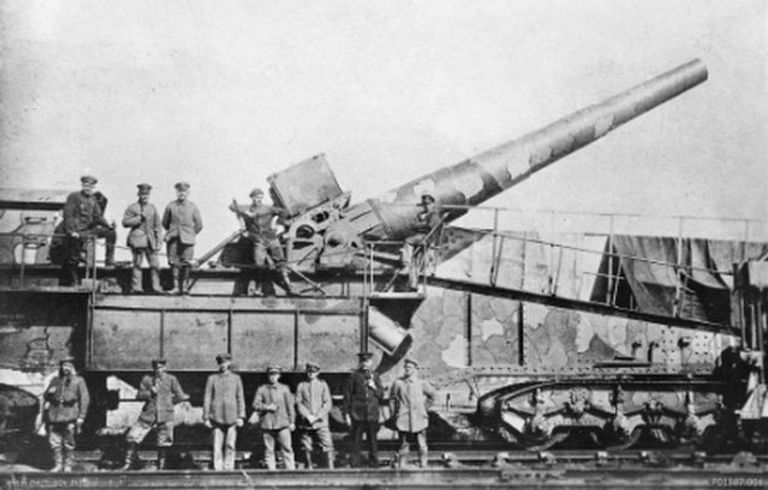

German Troops pictured with the Amiens Gun prior to its capture by the Australian Sappers

But the story doesn’t end here. 200 metres onward, in ‘no-man’s land”, there was a massive gun placed on a railway line, too large to be fired on normal terrain. Three Sappers, Lieutenant George Burrows, Sapper Les Strahan and Sapper John Palmer made the dangerous decision to cross no mans land to take the gun, and they did so, all the while being fired at by the Germans. In the fashion of true engineers they managed to start the locomotive, hooking up the gun and disconnecting the carriages, and taking the gun as far from the Germans as possible via the railway track.

During that night, the rest of the engineer field company managed to transfer the train all the way back onto the Australian side by taking the railway tracks from the back of the train and then moving them to the front of the train, slowly and surely moving the massive weapon well into Australian held territory. This is now known as the Amiens Gun, and the enormous barrel of the Amiens Gun can be seen at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra today.

The names of the three Sappers, Burrows, Strahan and Palmer were written out of history – the books written at that time mention only the 31st Infantry Battalion in the capture of the gun.

These Sappers, all mentioned here by name – Dean, Campbell, Burrows, Strahan, and Palmer drifted into obscurity after their heroic feats, none sufficiently celebrated for what they did. How many other Combat Engineers may have contributed to the successes of wars around the world and never received their due?

Up until 2022, there was no memorial dedicated to the World War One, Australian Corps of Engineers anywhere in the world. There is now a Bridge of Friendship located in ANZAC Park, Toowong in Brisbane as a monument to those Australian military engineers and a twin bridge to this one will be dedicated on 24 April 2024 located in the City of Amiens in France. These Friendship Bridges proposed by George and his team will, at long last, honor these men and their work. It will also be a celebration of the special relationship between the French people of Amiens and the Australian soldiers. The people of Amiens carry a longstanding sentiment of momentous appreciation for the Australian contribution to the success of the war and their help in saving their city from German capture.

The fund for the Amiens Bridge is supported by the Royal Australian Engineers Foundation. If you would like to support the construction of the Amiens Bridge, you can do so at raefoundation.org.au/product/one-time-donation